THE RISE OF CANADIAN ART

February 21, 2019 on Lessons, News by steveA VOICE OF OUR OWN

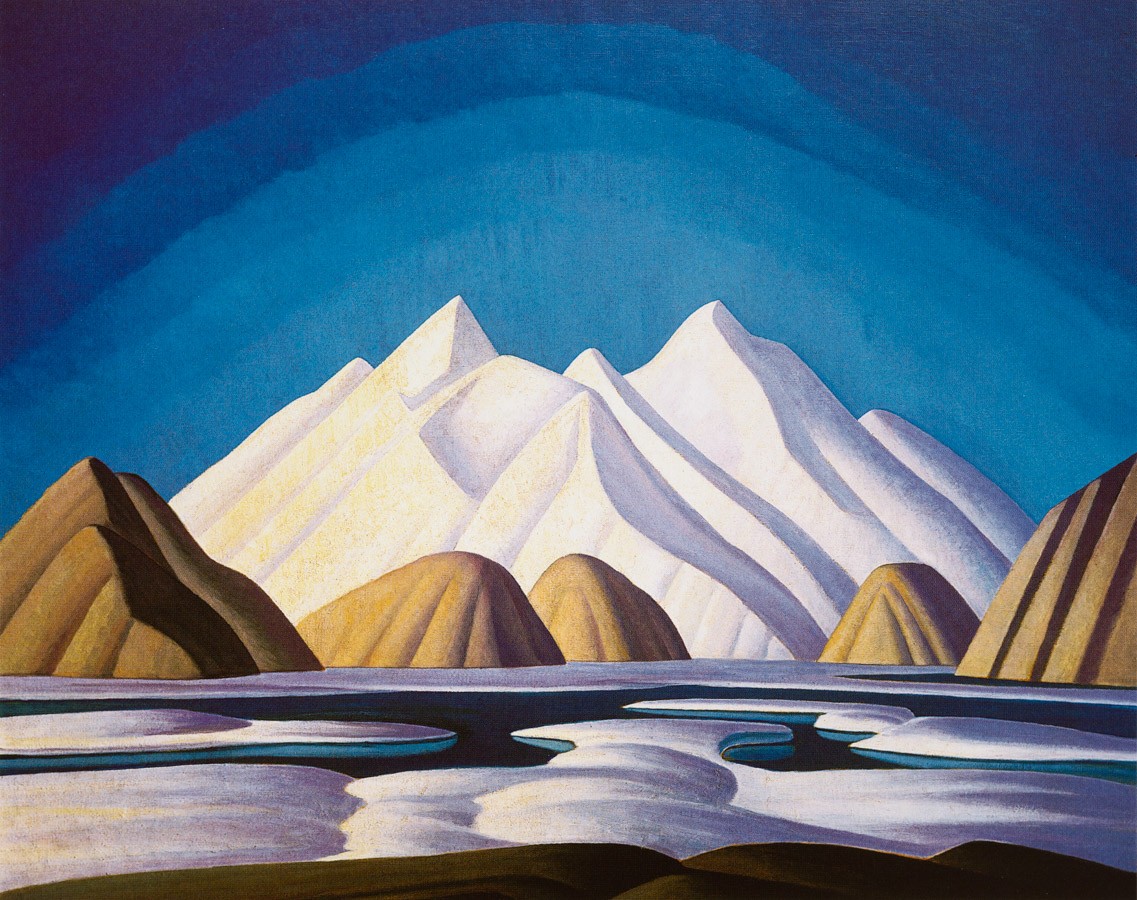

Between 1920 and 1933, a group of landscape painters called the Group of Seven aimed to develop the first distinctly Canadian style of painting. Some of them were influenced by Europe’s current popular Art Nouveau style. Their approach was close to painters from the past as they both worked in the studio and on the motif but their vision was highly influenced by modernist attitudes towards the arts and nature.

Members were Franklin Carmichael, Lawren Harris, A. Y. Jackson, Frank Johnston, Arthur Lismer, J.E.H.MacDonald, and Frederick Varley. Harris helped to fund many of the group’s wilderness excursions by having custom box cars outfitted with sleeping quarters and heat, then left at prearranged train track locations to be shunted back when the group wanted to return. This was possible due to Harris’ family fortune and influence. He later helped along with others to fund the construction of building for some of the group’s use as studio space in Toronto.

Contrary to some popular belief, B.C. painter Emily Carr never became member. Tom Thomson often referred to, but never officially a member, died in 1917 due to an accident on Canoe Lake in Northern Ontario.

In the 1930s, members of the Group of Seven decided to enlarge the club and formed the Canadian Group of Painters, made up of 28 artists from across the country.

THE QUEBEC CONNECTION

The Eastern Group of Painters was a Canadian artists collective founded in 1938 in Montreal, Quebec. The group included Montreal artists whose common interest was painting and an art for art’s sake aesthetic, not the espousal of a nationalist theory as was the case with the Group of Seven or the Canadian Group of Painters. The group’s members included Alexander Bercovitch, Goodridge Roberts, Eric Goldberg, Jack Weldon Humphrey, John Goodwin Lyman, and Jori Smith. Goldberg and Lyman were both well represented by Max Stern’s Dominion Gallery in Montreal.

Feeling somewhat left out of the Ontario based attitude held by, notably the Group of Seven the Eastern Group of Painters formed to counter this notion and restore variation of purpose, method, and geography to Canadian art.

John Lyman’s Contemporary Arts Society (1939–48) (in French, Société d’art contemporain) evolved out of the Eastern Group of Painters.

Prior to this association, Montreal finds itself the cradle of the Beaver Hall Group that formed within students of William Brymner. Notable for its equalitarian quality – admitting women and men equally – the Beaver Hall Group has become somewhat associated with women artists and has yielded notable painters such as Nora Collyer and Prudence Heward, to name a few.

REGIONALISM

By the 1930s, Canadian art was becoming a real thing but, inevitably, such a large country started to create regional art movements.

Emily Carr, British Columbia best known and emblematic artist became famous for her paintings of totem poles, native villages, and the forests of her native province.

Ontario’s David Milne, in his later years, experimented with content far removed from the simple, albeit highly original, landscapes that make up the better part of his oeuvre. Although he had espoused a pure aestheticism in his younger years (insisting that a painting’s content was merely secondary) he went on to produce a number of works that invite an allegorical interpretation.

Alberta’s William Kurelek would become known for his highly symbolic work featuring subjects out of his deeply religious upbringing but also marked by his ever present mental health problems.

In Quebec, John Goodwin Lyman founded The Contemporary Arts Society in 1939, promoting post-impressionist and fauvist art.

By the 1940s, Quebec would also become a hot spot for abstract art with the Automatistes.

THE RISE OF ABSTRACTION

Les Automatistes were a group of Québécois artistic dissidents from Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The movement was founded in the early 1940s by painter Paul-Émile Borduas. Les Automatistes were so called because they were influenced by Surrealism and its theory of automatism. Members included Marcel Barbeau, Roger Fauteux, Claude Gauvreau, Jean-Paul Riopelle, Pierre Gauvreau, Fernand Leduc, Jean-Paul Mousseau, and Marcelle Ferron and Françoise Sullivan.

The movement was born as much as an artistic statement as it was political at a time when most intellectuals in Quebec felt the stifling effect of the politics of Premier Maurice Duplessis at a time now known as “the Great Darkness”

In 1948 Borduas published a collective manifesto called the Refus global, an important document in the cultural history of Quebec and a declaration of artistic independence and the need for expressive freedoms.

Stylistically, it is worth noting that in accordance with the “revolutionary” attitude of the group, all the participants had a completely different artistic approach.

Although the group dispersed soon after the manifesto was published, the movement continues to have influence, and may be considered a forerunner of Quebec’s so-called Quiet Revolution.

Some of the best known alumni have now become extremely collectable on the global art market. Works by Borduas, Riopelle and Ferron can now fetch hundreds of thousands of dollars at auction and are part of some of the world’s major museum collections.

CONTEMPORARY ART

The 1960s saw the emergence of several important local developments in dialogue with international trends. In Vancouver, Ian Wallacewas particularly influential in nurturing this dialogue through his teaching and exchange programs at Emily Carr University of Art and Design (formerly the Vancouver School of Art), and visits from influential figures such as Lucy Lippard and Robert Smithson exposed younger artists to conceptual art.

In Toronto, Spadina Avenue became a hotspot for a loose affiliation of artists, notably Gordon Rayner, Graham Coughtry, and Robert Markle, who came to define the “Toronto look.”

In Quebec, faithful to the province’s iconoclastic tradition, the 1950s and 1960s mark the emergence of artists such as Fernand Leduc, Claude Tousignant, Cosic, Guido Molinari and other who will leave their mark by their innovative approach very much in sync with the rest of the planet.

In the new millennium, as is the case everywhere, art has become so much more than painting. Performance art, photography and other multimedia endeavours are now the norm while painting, in its many guise, remains as healthy as ever.